Against Flatness

Andrew Holmes

I have always been fascinated by Holmes’s imagery and the pandemic provided a unique opportunity to explore his work from a new perspective. Viewed digitally, these drawings appear so flawless that it is almost impossible to detect their medium and their means of production. Beyond their technical resolution, the images speak for themselves. They hold a power that captivate the viewer and capture a particular mood. Take ‘Make Call’ for instance, there is an unsettling stillness to the surface, the flow of daily life has been interrupted and a seemingly ordinary moment is frozen in suspense.

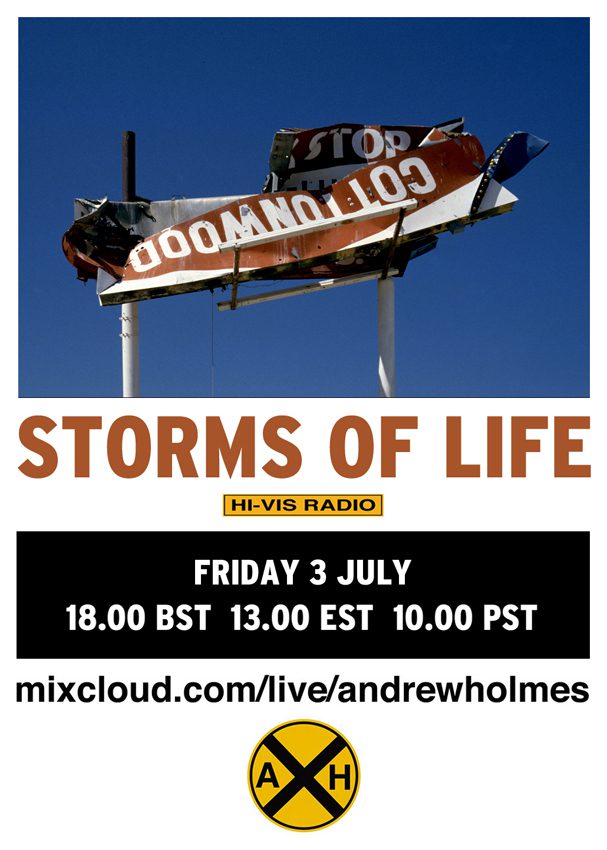

Since May 2020, Holmes has been hosting a weekly Hi-Vis Radio series online. Every Friday 18:00 a themed playlist is accompanied by a series of images, taking one on a journey of unusual, raw and often under-explored soundscapes. They opened up new insights into Holmes’s work by placing it in a wider countercultural context. Last week, I had an opportunity to speak with Andrew about his work, in order to better understand the drives behind his unique observations.

We began the conversation talking about his recently completed drawing ‘Make Call’.

‘…the freeway became the ultimate “Americanness”, the great American national delusion…’Nina Shen-Poblete [NSP]: The drawings you make are distinctively different from the photographs you take. There is a quality to the drawings that captivates you and you can’t quite figure out what it is. They kind of suck you in, and demand you to examine the whole image very carefully. Looking or scanning the image itself becomes a very interesting experience. strong>Andrew Holmes [AH]: When people talk about the drawings, ‘this must have taken a long time to do’ is always the first question I’m asked, ‘there must be something important here, that someone has found this to be of great importance to spend so much time on it’. At the ‘Whitechapel Open’, one of my drawings was displayed to the left-hand side of a photograph (not my photograph) and both images were about the same size. Observing the viewers’ reactions, I noticed that there would usually be one person who looked at the photograph and left, but there would be a dozen people queuing to look at the drawing. Considering the average time people take to look at a work of art at the Tate, around 15 seconds, the people there (in front of the drawing) would be taking an average 4-5 minutes, and they were looking within 4 inches or 100 mm of this image, scanning all over it. I remember Doris Saatchi (Doris Lockhart at the time) when she came to the house to have a look at the drawings as she started out by professing her interest in Realist Art, she commented that these drawings are completely unlike anybody else’s. Because as you get closer to the image, it does not break down and remains sharp. But if you were to see a painting by Rembrandt for instance, when you get close to it you begin to see the flying brush strokes, and the image only begin to make sense when you are about 15 feet away from it. But with mine, you can walk backwards and forwards, and it would remain the same at every distance.< [NSP]: That’s very interesting – would you say the drawings are very ‘flat’ in that sense that they do not ‘pixelate’? [AH]: It is the same all over – what’s interesting about the photograph at Whitechapel for instance, it was grey although it was a colour photograph. That’s because the blacks weren’t black, and the whites weren’t white. [NSP]: That’s a really interesting optical and visual experience which these colour drawings are uniquely able to provide, quite distinct from other media say a realist painting or a photograph. I wish to understand something that you alluded to earlier, about the kind of subconscious estrangement, if you like, an element in the drawing that is at once familiar and bizarre, which I think also contributes towards its unsettling quality. Perhaps this lies in the way in which you put the images together, how you select the subject matter, the way you densify layers and meanings, some may not be apparent on the first glance?

‘It’s not any phone box, and not any car, and not any restaurant with a parking lot. It’s about the three things coming together in a perfect moment’.

[AH]: [Referring to ‘Make Call’] It’s not any phone box, and not any car, and not any restaurant with a parking lot. It’s about the three things coming together in a perfect moment. A lot of assumptions have been made about my photographs, liking them to the Bechers’, but Tom Crow pointed out the fact that the things I see, are only there for a split second, maybe literally as long it takes to take a photograph. Then it is gone, vanished. In the case of the Bechers’, the subjects they photographed were there for sixty, seventy or even a hundred years, but that’s not what I’m interested in. I am an architect and when I return to the site, the restaurant would have gone, and something else would have been built there in its place. The telephone box would no longer exist, the car might still be there but everything else would have been replaced.

A lot of Spanish guitars are very beautiful. But it came to a point when you watch Chuck Berry play – he could play any shaped guitar, as did Bo Diddley – Diddley’s guitar was a rectangle – but it made no difference whatsoever to the sound. But what IS important is that Chuck Berry always played a cherry red Gibson, and Bo Diddley always played his customised rectangular guitar. So these were theatres – it was to do with the look of the thing which had nothing to do with the function, but ALL to do with what we now call the ‘image’, and ‘performance’.

When I started the project [of the 150 pencil drawings] I knew it would take forty or fifty years to complete, and that everything all had to be of the same size. My analysis of the late 20th century concludes that the only significant thing about it is the production of identical objects. Cars are quite a good example, and trucks are better examples as they change more slowly, less to do with fashion. But cars are interesting because they are the first industrial object designed for women and men, and they are not symmetrical. There is the female side of the car, and also the male side. This is unique. It was also the first time that industrial design became design-as-theatre, which was not a modernist idea at all. I used to talk about the electric guitar. A lot of Spanish guitars are very beautiful. But it came to a point when you watch Chuck Berry play – he could play any shaped guitar, as did Bo Diddley – Diddley’s guitar was a rectangle – but it made no difference whatsoever to the sound. But what IS important is that Chuck Berry always played a cherry red Gibson, and Bo Diddley always played his customised rectangular guitar. So these were theatres – it was to do with the look of the thing which had nothing to do with the function, but ALL to do with what we now call the ‘image’, and ‘performance’. Interestingly last week when I posted a drawing on Facebook, someone commented: ‘I had a car just like this, and it had a velour interior!’ What is interesting is that unlike leather or plastic, velour is a completely dysfunctional material in terms of design! It was chosen purely based on touch – literally the feeling when your fingers touch it, and when you slide your bottom along the seat, presumably having a girlfriend on your right side (since it is in America), so that you can slide your arm along the back along the bench seat… and of course, the car is the site of romance, death, and everything you can possibly think about really.

[NSP]: Do you think that this culture of automobiles and highways are a uniquely American phenomenon, which seems to be a recurrent theme in your work?

[AH]: It is based on the great American delusion of ‘freedom’. The car and the freeway are just the opposite of being free. You have to obey the rules or you are dead – it is the ultimate discipline driving on the American road. I’m interested in a nation that is mechanistic in its way of thinking. Discipline is permeated through the American culture in the worst possible sense, which is great if you are driving on a freeway – you don’t want anybody to be inventive. When I started the body of work, the freeway became the ultimate ‘Americanness’, the great American national delusion.

[NSP]: Would you say this particular culture or national psyche also gives rise to a certain kind of counter-cultural resistance, allowing an outburst of creative force that does not conform to rigid disciplines?

We all do the same thing, all grew up in the same systems, all drive on the road in the same way, all wear buttoned-down shirts. How do you become an individual?

[AH]: The challenge is how do you become an individual in a nation of over 300 million people? We all do the same thing, all grew up in the same systems, all drive on the road in the same way, all wear buttoned-down shirts. How do you become an individual? People like Mario De Alba, or Bob Spina, who is the world’s greatest painter, and probably Mario de Alba is the world’s greatest designer. They do it for themselves and they understand where that culture comes from. Mario is Mexican, who came to American when he was sixteen or seventeen, learnt about cars, also he was familiar with the Catholic iconography when he was growing up, so all these elements come together in the thing he makes.

[NSP]: These figures you are referring to, Mario De Alba and Bob Spina are legendary designers and painters of custom cars, especially the Lowriders. As an antidote to the great American delusion, would you say this ingenuity comes from a strong tradition of being hands-on?

[AH]: Trade – they are not frightened of learning a trade skill. My friend Michael went to sign painting school for two years to learnt sign painting freehand. It took him two years to learn to paint a line. Bob Spina did the same with the paint striper, it took him 3-4 years to do a line 3mm wide, consistently and straight. It takes a long time to learn something that is apparently very simple, and what he has done with it is just extraordinary. His designs are nearly always symmetrical, and I asked him whether he draws on a piece of paper and fold it over, then trace it so you get a perfect replica, he says ‘no I do it by eye’. That is phenomenal and he could just do it, every time and absolutely perfect.

[AH]: [Referring to ‘Make Call’] It’s not any phone box, and not any car, and not any restaurant with a parking lot. It’s about the three things coming together in a perfect moment. A lot of assumptions have been made about my photographs, liking them to the Bechers’, but Tom Crow pointed out the fact that the things I see, are only there for a split second, maybe literally as long it takes to take a photograph. Then it is gone, vanished. In the case of the Bechers’, the subjects they photographed were there for sixty, seventy or even a hundred years, but that’s not what I’m interested in. I am an architect and when I return to the site, the restaurant would have gone, and something else would have been built there in its place. The telephone box would no longer exist, the car might still be there but everything else would have been replaced.

A lot of Spanish guitars are very beautiful. But it came to a point when you watch Chuck Berry play – he could play any shaped guitar, as did Bo Diddley – Diddley’s guitar was a rectangle – but it made no difference whatsoever to the sound. But what IS important is that Chuck Berry always played a cherry red Gibson, and Bo Diddley always played his customised rectangular guitar. So these were theatres – it was to do with the look of the thing which had nothing to do with the function, but ALL to do with what we now call the ‘image’, and ‘performance’.

When I started the project [of the 150 pencil drawings] I knew it would take forty or fifty years to complete, and that everything all had to be of the same size. My analysis of the late 20th century concludes that the only significant thing about it is the production of identical objects. Cars are quite a good example, and trucks are better examples as they change more slowly, less to do with fashion. But cars are interesting because they are the first industrial object designed for women and men, and they are not symmetrical. There is the female side of the car, and also the male side. This is unique. It was also the first time that industrial design became design-as-theatre, which was not a modernist idea at all. I used to talk about the electric guitar. A lot of Spanish guitars are very beautiful. But it came to a point when you watch Chuck Berry play – he could play any shaped guitar, as did Bo Diddley – Diddley’s guitar was a rectangle – but it made no difference whatsoever to the sound. But what IS important is that Chuck Berry always played a cherry red Gibson, and Bo Diddley always played his customised rectangular guitar. So these were theatres – it was to do with the look of the thing which had nothing to do with the function, but ALL to do with what we now call the ‘image’, and ‘performance’. Interestingly last week when I posted a drawing on Facebook, someone commented: ‘I had a car just like this, and it had a velour interior!’ What is interesting is that unlike leather or plastic, velour is a completely dysfunctional material in terms of design! It was chosen purely based on touch – literally the feeling when your fingers touch it, and when you slide your bottom along the seat, presumably having a girlfriend on your right side (since it is in America), so that you can slide your arm along the back along the bench seat… and of course, the car is the site of romance, death, and everything you can possibly think about really.

[NSP]: Do you think that this culture of automobiles and highways are a uniquely American phenomenon, which seems to be a recurrent theme in your work?

[AH]: It is based on the great American delusion of ‘freedom’. The car and the freeway are just the opposite of being free. You have to obey the rules or you are dead – it is the ultimate discipline driving on the American road. I’m interested in a nation that is mechanistic in its way of thinking. Discipline is permeated through the American culture in the worst possible sense, which is great if you are driving on a freeway – you don’t want anybody to be inventive. When I started the body of work, the freeway became the ultimate ‘Americanness’, the great American national delusion.

[NSP]: Would you say this particular culture or national psyche also gives rise to a certain kind of counter-cultural resistance, allowing an outburst of creative force that does not conform to rigid disciplines?

We all do the same thing, all grew up in the same systems, all drive on the road in the same way, all wear buttoned-down shirts. How do you become an individual?

[AH]: The challenge is how do you become an individual in a nation of over 300 million people? We all do the same thing, all grew up in the same systems, all drive on the road in the same way, all wear buttoned-down shirts. How do you become an individual? People like Mario De Alba, or Bob Spina, who is the world’s greatest painter, and probably Mario de Alba is the world’s greatest designer. They do it for themselves and they understand where that culture comes from. Mario is Mexican, who came to American when he was sixteen or seventeen, learnt about cars, also he was familiar with the Catholic iconography when he was growing up, so all these elements come together in the thing he makes.

[NSP]: These figures you are referring to, Mario De Alba and Bob Spina are legendary designers and painters of custom cars, especially the Lowriders. As an antidote to the great American delusion, would you say this ingenuity comes from a strong tradition of being hands-on?

[AH]: Trade – they are not frightened of learning a trade skill. My friend Michael went to sign painting school for two years to learnt sign painting freehand. It took him two years to learn to paint a line. Bob Spina did the same with the paint striper, it took him 3-4 years to do a line 3mm wide, consistently and straight. It takes a long time to learn something that is apparently very simple, and what he has done with it is just extraordinary. His designs are nearly always symmetrical, and I asked him whether he draws on a piece of paper and fold it over, then trace it so you get a perfect replica, he says ‘no I do it by eye’. That is phenomenal and he could just do it, every time and absolutely perfect.

‘Country music is interesting because it is the MEN who display the emotion – the American men are not supposed to exhibit emotions, but theirs are the most heart rendering songs in musical history.’[NSP]: During the lockdown, I have been following your drawing progress on Facebook, as well as the Hi-Vis Radio regularly broadcast on Fridays. The themed soundtracks, the slideshows, and these drawings, they all came together. [AH]: It is the same idea driving them all. [NSP]: Is it the same principle that you use to assemble the playlist when you combine your images? [AH]: I was talking the other day to someone about what makes one a great country artist and others just don’t have it. Of course country music and gospel music are very different kinds of music. Country music is interesting because it is the MEN who display the emotion – the American men are not supposed to exhibit emotions, but theirs are the most heart rendering songs in musical history. It is often combined with humour, as a disguise for the upset of the emotion. You don’t necessarily have to have gone through the emotion to convey it, but it helps of course. Compared with gospel music, which is the most complex folk music in the world and requires huge amount of techniques, a bit like Michael practising his lines. To watch the Blind Boys of Alabama perform is just an incredible experience, because they know exactly what they were doing, and they knew how to create the emotion in the observer, they knew all the triggers to press, so it was also a technical exercise. But like Mario de Alba, they understand the origins of the emotions they try to convey, and they are deep emotions. Then it’s the techniques which could be repeated every night to an audience, who would be in tears in 30 seconds. When I went to see the ‘Mighty Cloud of Joy’, there were six nurses in attendance and they were all needed, people broke down. This ability to convey emotion in a very simple way, as in country music, or in a more complex way as in the gospel music interests me. This is what the ‘compression of meaning’ is about. The images do it and the music does it, too. So you can travel in your car and you see the world differently.